Where to Begin?

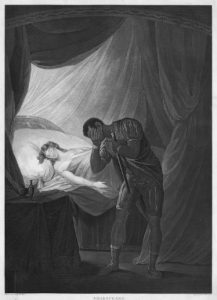

The neat thing about sharing Shakespeare with students is that there are so many ways to do it. My favorite method is still to read an entire play aloud as a group, and as often as possible to combine that with watching a live performance of the play. Which is why I’ve finally decided to start this school year with The Taming of the Shrew: American Shakespeare Center’s traveling troupe will be performing it in our area in early February, so reading it this fall will make for a fuller experience for all of us. (By the way, the feature image for this post, as well as all of the other images except the last, are different scenes from The Taming of the Shrew.)

More Exciting Ideas

But after attending two different teacher/adult events in Staunton, Virginia (home of the American Shakespeare Center) I’m working on how to add a little variety to our readings. Here are some of the ideas from their recent teachers seminar that I am considering adding to this fall’s lesson plans:

Walk Throughs

- To introduce the play, give everyone a name tag with the name of a major character and then do a “walk through” of the basics of the play, using a play summary from any number of websites or books. In the past, we’ve discussed the basic plot of plays before we’ve read them, but a walk through sounds like a great way to actually get the students up and moving. For our walk through I’ll probably compare what I have in Sharing Shakespeare with Students with the “Stuff that Happens” section in the American Shakespeare Center Study Guide for The Taming of the Shrew, but you can also find plot summaries in several other books about Shakespeare (Shakespeare for Dummies being one) and on the internet in numerous places, including: http://www.nosweatshakespeare.com/play-summary/

Read-Around

- I’ve traditionally passed out specific parts to students, so that they can “own” a character throughout the play, but this year I’ll probably be trying the “read-around” method for at least some portions of the play. With that, one student just starts reading the first line in a scene and reads until they get to a stopping point – a period, semi-colon, colon, or question mark. Then the next student reads a line, and so forth. We tried it at the teachers seminar I was just at and I could see advantages to reading that way for some portions of a play – for example, when a character has a particularly long set of lines to read. I still plan to have characters assigned for much of our reading, but we can vary it this fall and see how it goes.

Embedded Stage Directions/Props

- Embedded stage directions/props are interesting to pay attention to: Shakespeare gave very few actual stage directions in his plays. (“They fight” being one of his most popular.) But oftentimes directions are embedded into the lines of other characters – for instance, when one character tells another character to stand up. Or a prop might be mentioned when one character discusses the letter they are holding. Shakespeare didn’t need to write separate directions for those, he just included them within the lines of his characters. And often a single word tells us much: we can deduce that “this fellow” is closer to the speaker than “that fellow.”

- At other times actors have decisions to make: When, in the first scene of Taming of the Shrew, does the Hostess leave, when her line is “I must go fetch the head-borough.”? Does she leave as she’s saying the line, or directly after saying it? And right after that, when the directions say that the Beggar “Falls asleep” – did he sit or lay down at some point before the next line is spoken? Again, interesting questions for students to consider.

Different Ways to Read a Line

- It could also be helpful to have students slow down while reading certain portions and try various ways to say the same line. For instance, what different ways could Katherine say “Then God be blessed, it is the blessed sun.” in Act 4, Scene 6 of The Taming of the Shrew?

Who Are Lines Directed at?

- And in other places students can consider who the actor would be addressing with his lines. Lines weren’t always directed at another actor; sometimes they were directed at various audience members. That is something that American Shakespeare Center actors do particularly well. If you have the privilege of seeing them with students, it could be fun to have the students watch for that. (As I mentioned, I look forward to watching them perform in Huntsville, Alabama in early February 2018, as they do each year.)

Prose versus Verse

- Another exercise would be to have students determine whether a particular portion of a play is written in prose or verse. When each line starts with a capital letter, it is generally verse. Prose is written like you would expect to see regular sentences. With prose it can be helpful for students to see whether a character speaks in short sentences or run on sentences, and whether there are unfinished thoughts or questions are being asked. (If so, did anyone else complete the thought or answer the question?).

- There was another exciting lesson on iambic pentameter at the seminar – but I’m going to have to see if I can explain it well enough to my students before I try explaining it here! Suffice it to say for now, that Shakespeare wrote his lines in a variety of different ways.

What Would You Cut?

- I also saw an interesting concept in the study guide about having students determine how they would make choices about cutting out some of Shakespeare’s lines in order to make the play fit into a set amount of time. (Something directors have to do regularly.) For instance, if they were all tasked with removing 10% of the lines from a scene, which ones would they individually want to remove, and what might they agree on as a group?

Choose Somewhere to Start

And those are just some of the exciting ways we learned to make experiencing Shakespeare with students even more exciting than I’ve already found it to be. The wonderful thing about these ideas and the ones I’ve shared in previous posts is that sharing Shakespeare doesn’t have to be all or nothing.

And while I still have a personal preference of having students experience plays all the way through from beginning to end, I know that doesn’t work into everyone’s schedules. My plan for the fall is to work many of these different ideas in as we read through our next play, but I can also see how some of them would be useful even if you just had the time to do a scene or two with students. With Shakespeare, I may believe that more is generally better, but sometimes you just need a good place to start.

The Play’s the Thing

For more details on these and many other great activities, I can highly recommend the American Shakespeare Center’s Study Guides.

I plan to report back later this fall after we’ve tried out some of these activities in class. Regardless of what we think of each one, I’m confident we’ll still agree with Hamlet that “The play’s the thing.” (Even if he was talking about catching the conscience of a king with it and we’re “merely” trying to immerse students in the wonderful world of Shakespeare!)

Hamlet

Happy learning!

Cathy

For another one of our activities we were broken into small groups, each with a portion of a different scene. Each group had the same number of people as their scene had characters. As a group we had to choose five places from our scene that we could take “snapshots” of – where we could quickly “act” them out (more of a posed three-dimensional picture for each place.) The idea was to visually represent the highlights of our little scene.

For another one of our activities we were broken into small groups, each with a portion of a different scene. Each group had the same number of people as their scene had characters. As a group we had to choose five places from our scene that we could take “snapshots” of – where we could quickly “act” them out (more of a posed three-dimensional picture for each place.) The idea was to visually represent the highlights of our little scene. I don’t want to turn my Shakespeare classes into acting classes – plenty of others already offer those. I want to keep my emphasis on reading and enjoying Shakespeare. But I can see how these types of activities, sprinkled sporadically amongst our readings could add a new dimension to our Shakespeare understanding and enjoyment.

I don’t want to turn my Shakespeare classes into acting classes – plenty of others already offer those. I want to keep my emphasis on reading and enjoying Shakespeare. But I can see how these types of activities, sprinkled sporadically amongst our readings could add a new dimension to our Shakespeare understanding and enjoyment.